Every 3-5 years, the IwB takes on a major research project and develops its curriculum and special projects around the major project theme. Our major projects include Massive Change, the World House Project, and the City Systems Project. Our most recent research project is about Regional Ecologies. Each project is a stepping stone to a greater understanding of the role of design in shaping our world.

Massive Change

2003 – 2005

“Enormous in its scope, Massive Change is a wake-up call to everyone concerned with the ‘sustainability’ of the human race on earth.”

– Architectural Review

Over the last decades, design has begun taking on a more active role in shaping our world. Design conferences, interdisciplinary centres, and academic institutions have started to investigate the benefits of design theory and practice in solving the ‘wicked problems’ that face our world. The Institute without Boundaries has been at the forefront of these developments.

The IwB was started in partnership with Bruce Mau Design (BMD). In 2003, there were few programs in Toronto that taught students design thinking and/ or strategy in a hands-on format. Bruce Mau was already globally known for being a leader in design innovation and the School of Design at George Brown College had long been a thriving environment for education in the arts and design. Together the School of Design and BMD pioneered a program and design studio where students and experts could meet on an equal playing field and tackle real world problems together

The IwB’s first major project, Massive Change: The Future of Global Design, examined the role of design in addressing social, environmental and economic issues. In many ways, Massive Change was a revival of design theories from the 1960s, which stress the social benefits of design practice.

In the IwBs inaugural year, the Institute was commissioned by the Vancouver Art Gallery to create an exhibition and publication. Over two years, 14 students at the IwB researched, wrote, and designed the Massive Change exhibition, website, radio show and book in collaboration with the BMD Studio.

In 2004, Massive Change premiered at the Vancouver Art Gallery with a 20,000 square foot exhibition. The same year, Phaidon published the Massive Change book, and the student-designed Massive Change product line was launched by Umbra.

In 2005, graduates of the Institute collaborated with the School of Design at George Brown College to build the Massive Change in Action website for the Virtual Museum of Canada. The Massive Change exhibit also travelled to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and was seen by over 300,000 people by the end of its run.

The success of Massive Change sparked conversations on the potential of design to leverage positive change for the future. It also solidified the need for a permanent interdisciplinary institute that could develop and leverage design methods and practice to wicked problems affecting urban areas globally.

World House Project

2006 – 2009:

“In the earliest societies, the home provided the most basic needs of the community. Home was where there was food, water and protection from the elements. It was flexible and transportable, affordable and equitable, and fully integrated with the natural world. (..). We lived in full consciousness of the true cost of our shelter and sustenance, with a holistic view of our dependence on the system of the natural world.”

– IwB, System Home, 2007

How do we want to live? In his Nobel acceptance speech, Martin Luther King describes the world as a house and a family requiring a sharing of resources and equality of access to deal with racism and poverty, and promote equity and justice. The World House Project started from this notion and the understanding that our world as global village needs new concepts of shelter and home that balance human cultural, economic, climatic and terrain specific systems integral to the lives of all people.

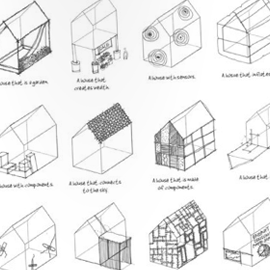

The World House Project was the second phase of the IwB’s research. It built upon the research and energy of Massive Change, and confronted the evolution of shelter for coming generations by developing housing systems based on principles of sustainability, accessibility, technological responsiveness and ecological balance.

The World House Project developed a three-year research plan broadly looking at the principles of holistic housing and its systems. The research was then applied to several case studies including affordable and flexible housing for the developing region of Costa Rica and suburban revitalization in Toronto.

The World House Project was an important development for the Institute. In its first year, the IwB moved from the BMD Studio into a newly renovated space at the School of Design at George Brown College and hired its own dedicated staff under the leadership of Luigi Ferrara, the Director of the School of Design. In this new structure, the Interdisciplinary Design Strategy program was developed as a unique postgraduate, hands-on and accredited educational program. The Institute also developed a special projects and a commercial division to conduct research and development and help clients with difficult challenges through a newly developed collaborative design methodology that built on the tradition of architectural charrettes. The new methodology was interdisciplinary, co-creative, collaborative, and used a whole systems approach. The renewed IwB curriculum focused on four key underpinnings: real time collaborative learning, whole systems design and design thinking, community engagement, co-creative and evolutionary design practices.

World House Themes by Year:

Year 01: Holistic Housing and Systems

In Year 01 of the World House Project, we partnered with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and the Harbinger Foundation, and looked at housing and shelter trends throughout human history and cultures. The research developed into several reports and systems diagrams exploring the social, ecological and political function of the home. The Systems Home report and the System Patterns in Housing Timeline (also known as “The World House Timeline”) both identified international housing and shelter through 12 systems, including communication, finance, waste, water, construction, etc. Focusing in on water as one of the twelve fundamental systems of housing design, the Institute also completed the Watershed: The World House Guide to Designing Water’s Future report that took a close look at the role of water systems in human construction. The IwB also developed and built the World House Living Model Version 1.

Year 01 of the World House Project showed that a systemic approach to housing could create a universal but locally adaptable model. By understanding the common systems in all housing and focusing on the creation process of the house rather than the end product, you can design a system that people can interact with. Thus, the house can evolve and appear as users need it, responding to changes and needs in peoples’ lives.

Year 02: Matapalo, Costa Rica

In the second year of the World House Project, the IwB began a partnership with Costa Rican Ministries of Culture and Housing. The project was spurred by the work of an IwB student and native Costa Rican, Giorgiana Penon, who uncovered an opportunity in her homeland. Penon’s initiative became a proposal for rural renewal in the developing Guanacaste region on behalf of the Costa Rican Ministries of Culture and Housing.

Matapalo, a small town in western Guanacaste, served as a case study. A former agricultural centre, the town was being overtaken by tourism development, driving living costs up and displacing locals. The IwB proposed viable housing solutions for Matapalo that were economically, culturally and environmentally suitable for the region, helping the Costa Rican Ministries envision better housing solutions for the future of the Guanacaste region. The project also verified the collaborative and co-learning principles of the IwB illustrating that a student initiative could become one of the Institute’s major curriculum project.

The results of the year were a green social housing prototype for rural areas, a model collaborative process for renewing small villages in the region, and a regional plan balancing global tourism.

On the whole, it was trying to find the balance in power relations in Matapalo that was the most difficult task. In Matapalo there are many inequalities and a delicate balance between local and global forces in Matapalo. Understanding power relationships in Matapalo meant not trying to decipher whether it is more local or global, but acknowledging the locally and globally enforced inequalities and forces that have shaped the city, and trying to find a balance of power.

Year 03: Suburban Revitalization

In our third major project for World House, our focus shifted back to North America. The Institute partnered with Habitat for Humanity Canada and Evergreen to renovate a neighbourhood in Toronto and to re-imagine a city without sprawl, a city that balances nature, people, income and access. The IwB took the Broadlands Boulevard in Don Mills as a case study of Toronto’s inner suburban neighbourhoods. The site analysis showed a suburb in need of drastic renovation. The focus of the third year of the World House Project became exploring the right way to renovate Toronto’s aging inner suburbs by starting from the inside and organically evolving space by making small scale interventions.The resulting proposal, Renovate Your Neighbourhood, is a catalogue and a toolkit that helps citizens revitalize their communities and partner with established not for profit groups like Evergreen and Habitat for Humanity. The catalogue offers step-by-step project ideas like ‘Re:novate Our Homes’ and ‘Re:purpose Our Small Suburban Mall.’

During the World House Project, the Institute also began expanding its community engagement. The IwB held several charrettes and the World House Interdesign Conference. The conference was a partnership with the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (Icsid). The event brought together 154 participants from around the world to explore and develop solutions for challenges related to housing and water for clients such as Downsview Park, Waterfront Toronto, the Town of Port Perry, and the Mount Dennis community. The charrettes and conference showed the valuable role the Institute could play in shaping communities locally and internationally. Before long other clients were beginning to ask the IwB to use its methodologies to help them solve some intractable problems. Clients like Windsor Essex Community Housing, Sony Centre, TAS Design Build, Dublin City Council, Peel Living, Magna Aftermarket and many others, called on the IwB to consult and develop solutions for their challenges.

The Institute also completed numerous special projects, the most noteworthy of which was the Canuhome. Canuhome was an 850 square foot residence containing a kitchen, living room, dining room, bathroom and bedroom. It was exhibited 12 times, by IwB’s client, CMHC, in numerous cities and was viewed by over 500,000 people.

World House Highlights

Year 01: Holistic Housing and Systems

Year 02: Matapalo Costa Rica

Year 03: Renovate Your Neighbourhood

Major Special Project: Canuhome

City Systems Project

2009 – 2013

“The challenges of any city are not unique, isolated occurrences. Although the scale or scope of those challenges may vary, most issues are common to cities worldwide. By examining the systems that support a city, we can uncover new opportunities for innovation and improvement.”

– IwB, Universally Local, 2010

Since the Industrial Era, the rate of urbanization has skyrocketed. The city is everywhere and growing. As the primary human habitat, the city is the site for many ‘wicked problems’ affecting the lives of most people on the planet. The City Systems Project recognized that to look at issues of physical and social resilience and sustainability of the environment, it is necessary to look beyond the house to how cities themselves are built.

Thinking of current city infrastructure means realizing it is a reflection of theories past. Aldo Rossi refers to the city as an ‘artifact’, the landscape of a city is a testament to the different time periods and ideologies past and present. For Jane Jacobs, in the city there is a process of ‘filtering’, a natural renewal and recycling process of the physical infrastructure of the city. Cities are a patchwork of pieces built at different times, which means that those parts will also have to be renovated at similar times.

A large part of the 1940s to 1960s city infrastructure was built following 19th century building concepts. These evolved through experimentation in the 1920s and were then implemented on a mass scale in the 1940s and on. A great majority of infrastructure inspired by 19th century building concepts is utopian in nature in that it does not address the social needs of people actually using the infrastructure.

Most of our suburbs are coming to the end of their lifecycles and the question of how they will be adapted to the needs of the contemporary and future urbanites is extremely relevant. The City Systems Project proposed new ways to live and work in a contemporary city in a resilient way by reimagining the social and physical adaptability of infrastructure that will underpin the renewal of the city of the future.

City Systems Themes by Year:

Year 01: Flemingdon Park Community Rejuvenation

In the first year of City Systems, the IwB partnered with the Toronto Community and Housing Corporation. Examining the case study of Flemingdon Park, the IwB tried to understand how a piece of the city worked as a system, in this case a neighbourhood of about 15,000 residents.

Flemingdon Park has an aging housing stock built in the 1940s. It has an outdated layout and a lack of local amenities. The original architects of Flemingdon Park imagined social changes that never happened because they did not work with the residents to make them happen, thus, the reason why a lot of it’s infrastructure features are irrelevant to residents. The challenge was to rejuvenate this mid-twentieth century complex so that it responded to contemporary city residents’ needs and in the process build a model for a resilient, greener city neighbourhood for the 21st century.

The result was a development plan and prospectus for a revitalized Flemingdon Park and a book titled Universally Local that that proposed revitalization through seven characteristics: wellness, safety, accessibility, diversity, cohesion, identity, and sustainability. The book proposed that the solution to one city’s problems are local and that the solution to many cities’ problems are universally local. Further, it emphasized that coordinated local initiatives could produce systemic change. The Flemingdon Park project underlined the importance of revitalization that is not just about physical changes, but about social infrastructure changes as well, and about finding harmony between the two. Here the power of co-creation and emphasizing the citizens’ involvement is key to creating and recreating the city.

Year 02: Lota, Chile

In year two of City Systems, Lota, a small municipality in Chile, was brought to the IwB’s attention by the Latin American Canadian Art Projects (LACAP). LACAP, a Toronto arts organization, partnered with Lota after the February 2010 earthquake. Lota is a city stricken by poverty. One third of Lota’s population was left homeless after the 2010 earthquake; an economic slump plagues the city as well. The difficult problems facing this municipality were well matched with the IwB’s interdisciplinary approach of whole systems design and social innovation. Taking on the Lota project the IwB was able to examine the workings of the complete system of a small city.

In 2010, the IwB partnered with Lota and completed a revitalization plan for the community titled People Change Places. The study showed Lota’s most important asset is its human capital. The report responds to planning and design challenges outlined by the elected municipal government of Lota, and it is based on recommendations of citizens’ visions as understood through field research conducted by the IwB and its affiliates in Lota.

People Change Places became a lesson in proactive local action. The residents of Lota were perpetually ‘waiting’ for help. The community’s reliance on external motivation and aid lessened its ability to act from within. A place will change when everyone contributes in small and big ways to the changes. Working in South America and seeing the energy and determination of the local community was an extremely rewarding experience for the IwB. Students and faculty extended their experience in the realm of inter-cultural, politically charged projects and the limits and strengths of participation from design groups from abroad.

Year 03: Edge City, Markham

In 2011, during the third year of City Systems research, the City of Markham became a major project partner of the Institute. The IwB partnership took place at a crucial time during which Markham changed designation from a township, and a rapidly expanding suburb of Toronto, to officially being recognized as a city in 2012. The project allowed the IwB to move from investigating a small city like Lota to a larger one of approximately 250,000 people.

At the outskirts of Toronto, Markham is an ‘edge city’ in many respects, with homogenous residential areas, large distances, and little density to promote pedestrian culture. But it is also changing both spatially and demographically. It has a diverse and growing new immigrant population, and holds a powerful position as a high tech capital in Canada. Nonetheless, in some respects, Markham faces issues of an ‘incomplete’ city because it lacks a strong sense of community. To complete an edge city you have to create a dynamic whereby people work as a community. The focus of the project became how to complete Markham as an edge city by bringing together its diverse communities.

Through its research, the IwB realized what Markham needed most was a change lab where the right teams could meet to address the city’s identity and community building challenges. The IwB’s work became about demonstrating the usefulness and suitability of a change lab in Markham called COLAB. COLAB would be an onsite and online project and an interdisciplinary design solutions unit for Markham that creates a space where the political, social, design, business, and technical forces of innovation can meet and be leveraged in a neutral space. COLAB is a pilot for a virtual and physical space where Markham’s diverse stakeholders can practice community building and innovation.

Year 04: The Dublin Project, Ireland

Beginning in 2013, in the fourth year of City Systems, the IwB began a partnership with Dublin City Council (DCC), the municipal authority for the City of Dublin, and the city’s multidisciplinary unit called The Studio. Dublin is small in comparison to most world capitals, but is considered a ‘global city’. The Dublin Project moved the City Systems research to a larger scale by looking at a complete city system of a larger city with over a million residents.

Though Dublin is a ‘global city’, it is not expanding. It led Ireland’s expansion during the Celtic Tiger economic boom, but it also felt the equal brunt of the economic crisis starting in 2009. Dublin faces a host of challenges like derelict properties, rising crime rates, and a severely decreased budget to deal with these new problems. It is a major world city, with over a million people, that is struggling to provide its services, as a result its citizens have lost confidence in the municipality. DCC came to the IwB to rethink and adapt its service delivery.

In October and November 2012, the IwB students and staff spent five weeks doing research and working with DCC and The Studio staff in Dublin. Throughout 2012-2013, the IwB students presented small case studies to DCC suggesting cultural projects and agendas to encourage public engagement, urban regeneration projects to create better public spaces, and a range of propositions to create transparency and clearer communication between the city and the public. Ultimately, DCC choose the latter as the focus of the major project. The IwB students proposed Our Dublin, a system of programs intended to support and activate civic engagement and collaboration. Our Dublin responds to DCC’s aims to innovate and create intelligence around the issue of public engagement and to improve trust between the citizens and the municipal government.

City Systems Lessons:

The City Systems Project was structured on the belief that a city is a system of humanity, integral to the development of civilization. The ability to not just live but to thrive, expand and innovate in dense quarters has defined us as a species and shaped our culture and our lives. Through the City Systems major projects, the IwB was able to explore the city at various scales: from parts of the system (a neighbourhood) to the complete systems of a small city and larger city.

Seeing the city as an ‘artifact’ composed of time-specific parts, and in a constant cycle of decay and renewal meant thinking about infrastructure of the future as adaptable and growing. Importantly, it also meant seeing urban infrastructure fully connected to the needs and lives of residents. The IwB’s City Systems projects demonstrated that the physical and social considerations of a city’s systems and infrastructure must act in harmony. Further, community and identity are not given factors in the urban environment, they have to be cultivated and nourished because the city is constantly changing. It is the continuum of a community that makes a city complete, thus, the city requires spaces that nurture the meeting of its diverse stakeholders. The Institute’s projects from 2009-2013 tried to grapple with the growth in size and complexity of cities, understanding their human, ecological, technological and economic systems.

City Systems Highlights

Year 01: Flemingdon Park community rejuvenation

Year 02: Lota, Chile

Year 03: Edge City, Markham, Ontario

Year 04: The Dublin Project, Ireland

Major Special Project: Move – The Transportation Expo

Regional Ecologies

2013 – 2014

“As globalization proceeds, an extended archipelago or mosaic of large city regions is evidently coming into being, and these peculiar agglomerations now increasingly function as the spatial foundations of the new world system”.

– Allen J. Scott, “Globalization and the Rise of City-regions”, 2001

It is becoming widely recognized that there is a lack of understanding of the networks that tie together cities and regions. The world’s fifty largest city regions, on average, have twice as many people living outside the core city than in it (e.g. more people live in the Toronto region’s 905 area code than in the City of Toronto’s 416 area code). To fully understand and explore the challenges and opportunities of urbanization we need to work within a regional context.

Working at the regional level, however, adds layers of complexity. Large regions can have nation-sized economies that are made up of all scales from local to global. They embody a large variety of land usages from city-core to countryside, and have multi-jurisdictional, overlapping governance. Furthermore, regions are unconstrained by political borders, crossing provincial/state or even national borders, and their dynamic boundaries follow the growth of the region.

The Regional Ecologies Project expands on City Systems to consider urbanization as a regional phenomenon. Unlike cities, which tend to be well-defined entities with legal boundaries and a strong sense of place, city-regions are more nebulous, usually made up of a core city surrounded by suburbs, neighbouring communities and hinterland all contained within a continuous urban area. The IwB’s approach considers regions as a whole with the goal of understanding the systems of nature, culture, industry, infrastructure, governance, communication, and finance that support and connect regions locally and globally.

In the fall of 2013, the IwB launched a five-year Regional Ecologies research project to understand the complex networks and interconnected systems of innovation that define our regions and to design intelligent and balanced solutions that will foster prosperous, livable and resilient regions.

Regional Ecologies Themes by Year:

The Regional Ecologies Project will span five years and will be broken down into five different city-region types: Gateway Cities, Divided Places, Interstitial Zones, Symbiotic Cities, and Continuous Corridors. Importantly, these categories are not exclusive, they are research themes from which to build a greater understanding of city-regions. Each year, the Institute will conduct research, propose design solutions and apply its unique whole systems methodologies to real-life projects in collaboration with civic and industry partners around these central themes.

The Regional Ecologies five-year plan:

2013-2014 – Gateway Cities are at the heart of city-regions. They are leaders in economic, cultural, and political processes. ‘Global’ or ‘world’ gateway cities are beginning to bypass nation states as the key centres of global and regional socio-economic power.

2014-2015 – Divided Places are regions characterized by sharp and immediate differences in wealth, infrastructure, density, etc., where virtual and physical segmentation creates stark social, economic and political inequality.

2015-2016 – Interstitial Zones can be regions that have lost their primacy to global cities due to changes in trade flows, declining industries or geographic shifts in production. They can also be gateways for large, thinly-populated natural regions, zones of low-growth with the potential to redefine their role in a globalized economy.

2016-2017 – Symbiotic Regions are independent areas that are economically codependent with a neighbouring city or region, usually separated by a natural or jurisdictional border. Their symbiotic relationship means that they are part of a bigger system that strongly binds the two cities and their regions.

2017-2018 – Continuous Communities are regions with large and contiguous cities connected by high-speed rail, frequent flights, free trade zones, etc., creating continuous corridors of connectivity. These city clusters operate closely on multiple levels allowing people to live and work across places and cultures.

In September 2013, we started the first year of the Regional Ecologies project. Gateway Cities looks at three cities that serve as gateways to their respective regions–Toronto, New York City, and Chicago. Our aim is to understand and define the layers and patterns of regional systems in terms of energy, housing, transportation, and public spaces. We are currently, working on several deliverables of this project, one being a design of a Neighbourhood Integration Plan called ‘Airport City’ for our current partner the Greater Toronto Airport Authority.

A regional approach involves considering regions as a whole with the goal of obtaining new resiliency through greater cooperation, regional planning and governance. The Regional Ecologies project will take into account a wide variety of stakeholders, from small towns to big cities, and the systems of nature, culture, industry, infrastructure, governance and finance that support and connect them locally and globally. This project will identify opportunities for sustainable economic, social and environmental growth through existing and potential new relationships and networks.

Fundamentally, the city-region is neither the problem nor the solution, it is simply where the world lives. The complexity and diversity of the regional form is what makes a region resilient. The Regional Ecologies project hopes to better understand this complexity and propose relevant design solutions.

Regional Ecologies Highlights

Year 01: Gateway City – Toronto, New York, Chicago

Year 02: Connecting Divided Places

Year 03: Interstitial Zones

Year 04: Symbiotic Regions

Year 05: Continuous Communities