South Sudan Residential Shelter Charrette

Overview:

In 2005, the IwB was approached by representatives of the Hampton Group to investigate housing solutions for Southern Sudan. The IwB conducted a three-day design charrette executed by a small team of interdisciplinary professionals and invited guest experts. The charrette concentrated on achieving a modest, permanent residence that could provide essential living services for local families and/ or foreign aid workers. It looked at the City of Juba and the greater Equatoria region, the area in which the Hampton Group was most active.

__

The situation in South Sudan is complex and any new venture will ultimately need to consider its position within and impact on the country’s unpredictable context.

Project Goals:

To design housing solutions that consider Southern Sudan’s unsettled political climate, its limited material economy, service infrastructure, and skilled labour constraints, as well as the expense of overseas shipping. The project needed to meet the budget stipulations, be manufactured in Canada, and shipped internationally with a low shipping volume.

South Sudan Residential Shelter Charrette:

South Sudan is an area plagued by years of continuous conflict. Millions of people have been killed or have become refugees both inside and outside the country during its two civil wars, its ongoing internal strife, and external tensions with neighbouring countries. In 2011, South Sudan became an independent country from Sudan, but the independence did not ease the interethnic warfare and human rights violations plaguing the country. As a result of continuing large-scale warfare, services, amenities, and road access in South Sudan have been limited. There has been very little development of civic infrastructure since the fifties and the recent conflict has made it unlikely that development will resurge.

In 2005, there was a temporary development boom after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). President Salva Kiir Maydrit was developing a legal framework and guides that would encourage foreign investment in areas including agriculture, energy, mining, economic sustainability, industry, civic infrastructure, transportation, housing, animal resources, hotels, health, and education. At this time, there was a lot of interest in raising the standard of living in South Sudan and in setting up permanent residences for groups of expatriates who were returning to their homeland as well as providing temporary residences and work units for foreign aid workers.

Many of the NGOs which operated in South Sudan were located in the capital city of Juba. Like most of South Sudan, Juba and its surroundings do not have access to running water, waste treatment, or electricity supplied by a grid. In addition, amenities such as internet, television, or public libraries are rare. Juba’s population is estimated at 372,410, but like in most of South Sudan, it changes daily as many of its internally displaced persons (IDPs) return home or leave. The returning populations experience difficulties when trying to re-establish themselves. As a result of the ongoing conflict, their homes and all their possessions have been destroyed.

Many non-profit organizations bring their own shelters from their home countries. NGO compounds often begin with tents and then evolve to include permanent structures. Some groups also construct traditional shelters. In cities such as Juba, groups who do not own property typically stay in tent motels. A few of the tent motel complexes provide air conditioning, but other services, such as running water or lighting, are rarely available. Permanent hotel compounds have also been built, constructed from concrete block and corrugated steel. But there are many drawbacks to all of these types of shelter, including discomfort caused by a combination of heat, humidity, and insects.

The Hampton Group was an active aid company in South Sudan and wanted to deliver a customized housing solution that could suit the interests of South Sudan residents and/ or visiting foreign groups, like NGO workers. The Institute worked with representatives from the Hampton Group, the UN, and many industry experts to conduct the charrette.

The Hampton Group expressed interest in using a Canadian manufactured design option. The team evaluated six design typologies, all of which included some degree of prefabrication. In comparing their suitability as low-cost housing solutions for the Sudanese context, the team considered factors such as: ease of assembly, comfort, longevity, and return on investment.

In particular, the design team considered how the housing system would address the unique characteristics of the country: the strong family ethic of Sudanese populations, the unstable conditions that result from poverty and war, the physical challenges that result from the heavy rain, clay soil, termites and mosquitoes, the lack of existing or sufficient infrastructural support, the expensive cost of living in major urban areas, and the required job creation to employ returning residents.

Project Outcomes:

The design team evaluated the pros and cons of the existing design examples that could serve as inspiration for a housing system for South Sudan. The proposal outlined the design development for the project pilot with user engagement, the development of a business plan, the building of the prototype, the piloting of the project in South Sudan, and the revision of the pilot.

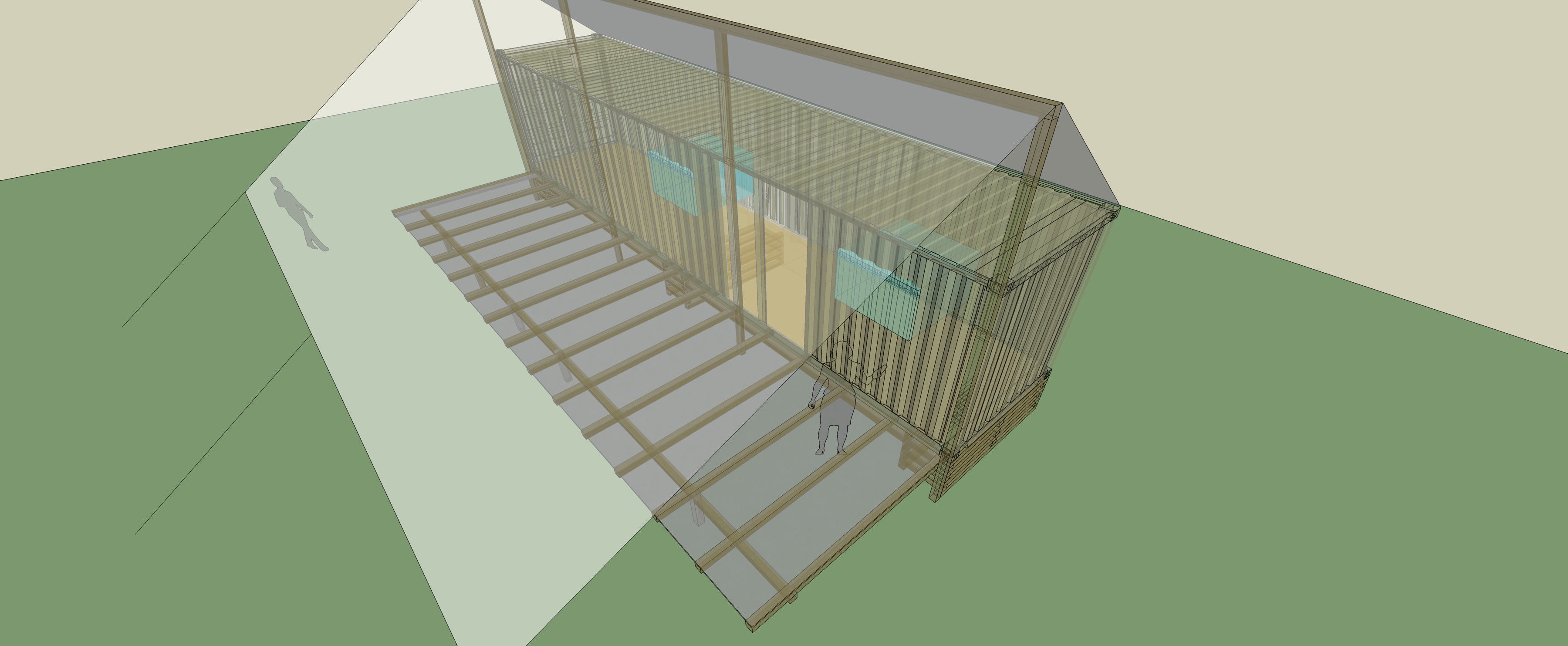

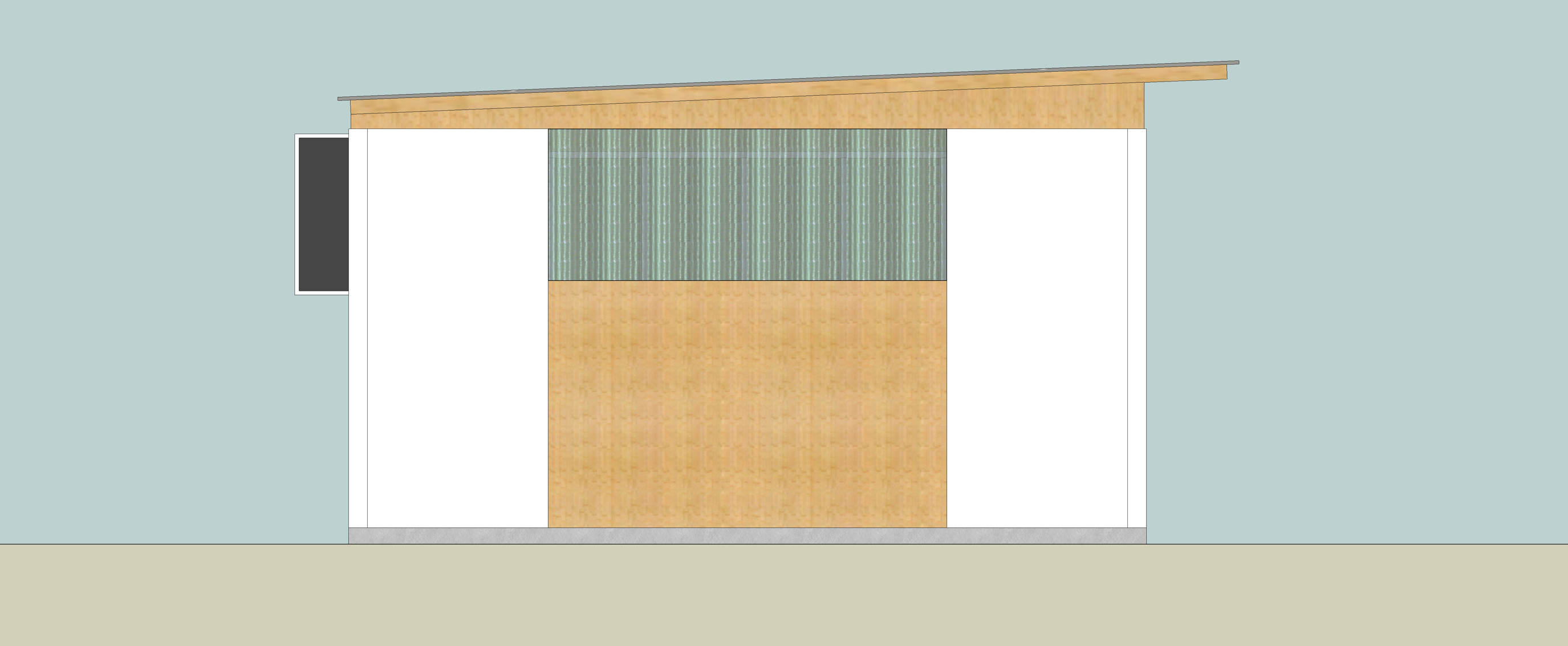

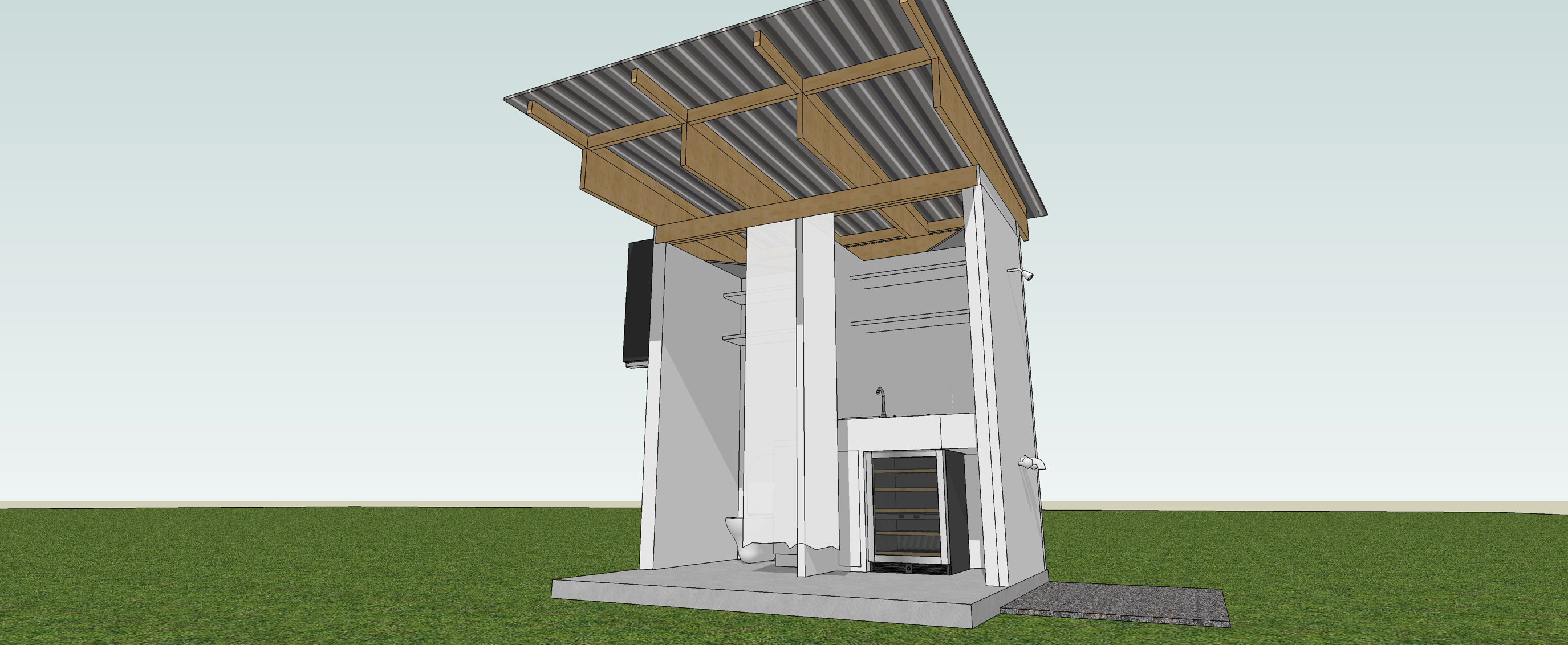

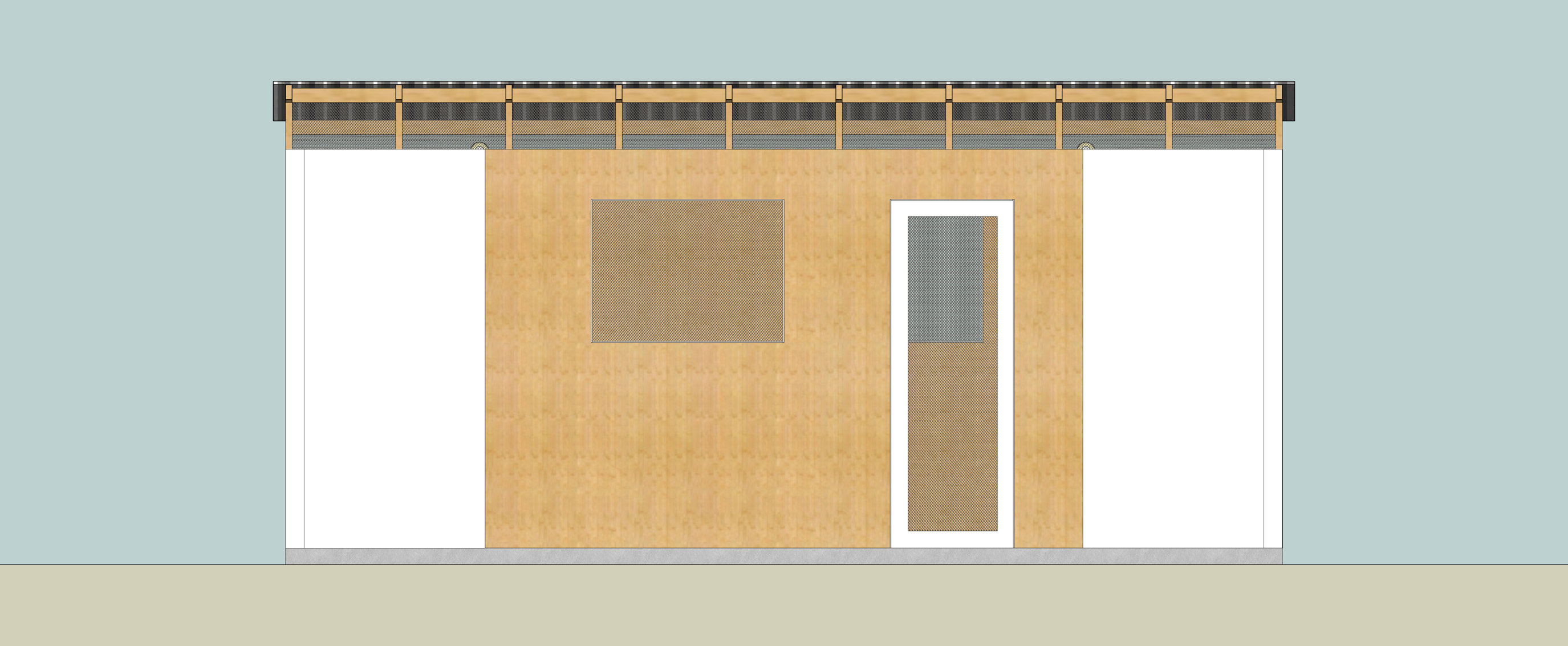

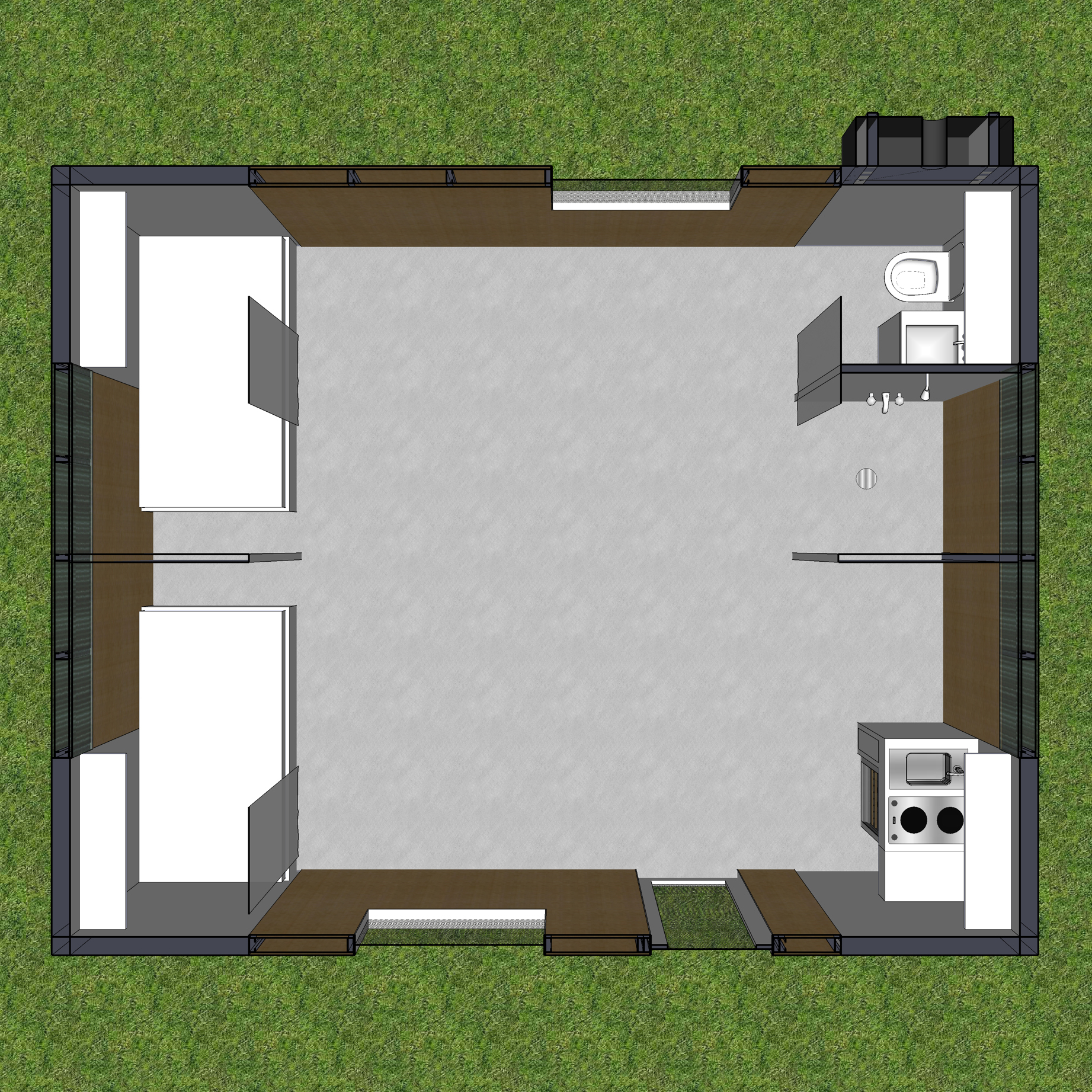

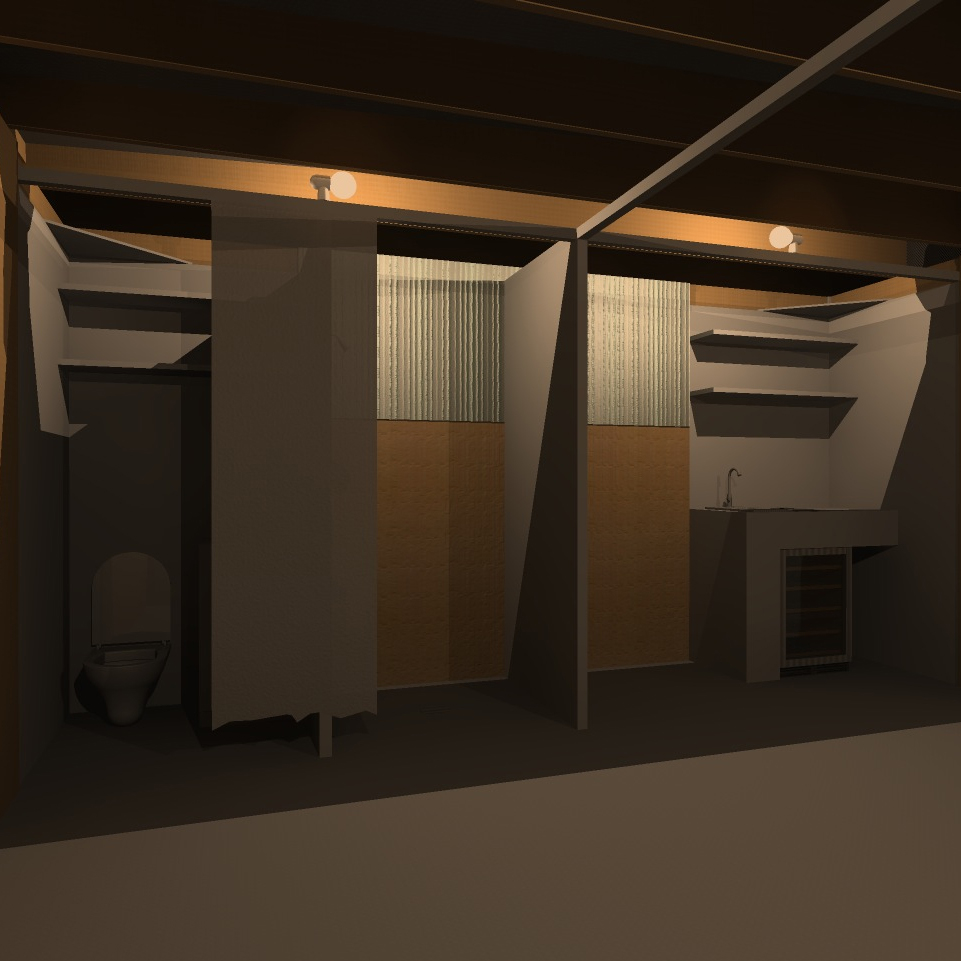

The proposed design was modular, flexible, and flat-packed, when developed further, it could also be adapted based on a site assessment as well as specific project needs. It was a ‘glocal’ solution with flat-packed panels and Canadian micro-products mixed with locally sustainable building materials and practices to create a hybrid housing solution that was partially Canadian and Sudanese, using strategic hi-tech and high knowledge building systems with low-tech local craft.

Importantly, it was measured and scaled for its cost efficiency. Based on a 40ft shipping container for transportation (assuming a shipping cost of $20-25K7 per container to Juba), the proposed shelter design showed that the economic feasibility of providing a Canadian-made product to Sudan is primarily dependent on maintaining a low shipping volume.

Given the ongoing need to provide adequate aid and shelter for the people of South Sudan and the various aid workers, the South Sudan residential Shelter Design Charrette results continue to provide a valuable and actionable housing blueprint adequate for the complex social and political dynamic of the country. If executed in close collaboration with local groups, this project could have a significant impact on the country’s economic capacity, sustainable development, and social well-being.

For a full description of the project see the South Sudan Residential Shelter Design Charrette Report.

Project Credits:

The Hampton Group

Harbinger Foundation

Luigi Ferrara

Connor Malloy

Silvio Ciarlandini

Marc Kennedy

Perin Ruttonsha

Evelyne Au-Navioz

Karl Johnson

Michael McMartin

Teresa Miller

Mark Watson

Michael Cassidy

Maurice Fuoco

Fernando Lopez

Patrick Malloy

Project Tags:

South Sudan, City of Juba, The Hampton Group, housing, shelter, residential, foreign workers, charrette

“If you build homes, people have a reason to stay…People had nothing to lose before, so fighting has almost become a way of life. Building something for them to care for and protect will make many not choose war in the future.”

– Yar Manoa Major, South Sudanese Returned Resident & Entrepreneur, From: Kun, K. Ed. “The World As We Don’t Know It: Possibilities for Enterprise in Sudan.” Corporate Knights: The Canadian Magazine for Responsible Business (Vol.7.2, 2008):16